Venda greets you before you even arrive. In the way the land rises, lush, mountainous, it’s alive. This is a place where culture is not just archived, but it is practised. Worn into the land, carried in language and rooted in the smallest gestures and materials, people return to again and again.

As Nguni people, our cultures have always been rooted in land, how we relate to it, draw from it, honour it, and return to it. Yet as we face increasing forces such as urbanisation, gentrification, cultural commodification, and the erasure that often comes with “development”, these relationships are gradually strained.

What was once shared by all becomes marketable, what was sacred becomes aesthetic, and what was inherited risks becoming forgotten.

With this, cultural preservation can not sit solely with cultural practitioners or elders. It is a shared responsibility of individuals, communities, institutions and the government. It is also a responsibility that artists are uniquely positioned to carry through interpretation, material exploration, and storytelling.

It was from this place that we participated in the “Pass It On” project. A seven-day cultural exchange tour to Venda, funded by The National Arts Council, executed by The Dealr, an artist-led digital art platform committed to ethical art trading and sustainable creative practice, whose work centres on building meaningful connections between artists, collectors, and place.

The tour was not only about meeting artists and cultural practitioners but also about engaging with the material memory of the land.

On the first night, we gathered around a fire beneath a sky filled with stars scattered wide and a full moon at the Manavhela Nature Reserve.

The lodge itself holds a layered history. Formerly known as the Ben Lavin Nature Reserve, the land originally belonged to the Manavhela clan before it was taken under the Group Areas Act and renamed. Like many landscapes in South Africa, it carries the quiet violence of erasure, a renaming, a removal and a rewriting. In recent years, the land has been restored to its rightful custodians, the Manavhela clan.

It felt meaningful that our first gathering took place here. On returned land, around a communal fire.

It was by this fire that we were introduced to the six artists joining the tour, alongside representatives from the alternative art platform. The group is made up of women from across the continent: Chuma Adam, Yonela Makoba, Swaline Mkhonto, Tinyiko Makwakwa, Katleho Habi, and Khanyisa Brancon.

As introductions circled the fire, it became increasingly clear why The Dealr had brought these particular artists into this exchange. Though distinct in medium and approach, their practices are united by a shared commitment to cultural storytelling. Each artist, in her own way, works to honour lineage, particularly black women and matriarchs who hold memory, ritual, and survival within their bodies.

The tour began with a visit to the Thohoyandou Arts Centre, where we were welcomed by Avhashoni Mainganye and Grace Tshikuvhe, who guided us through the space and its history. The centre functions as a creative home for young Venda artists, a place to experiment, to practice and to belong.

Inside the space, an abundance of intricate wood carvings, layered prints, and sculptural works are showcased in various stages of completion.

Spaces like the Thohoyandou Arts Centre are important within conversations of cultural preservation. Preservation is not only about protecting what already exists, but it is also about nurturing what is still forming. By providing young artists with access to materials, mentorship, and community, the centre ensures that cultural expression remains active rather than archived. It offers a place of refuge where emerging artists do not feel isolated in their practice and see possibilities reflected back at them.

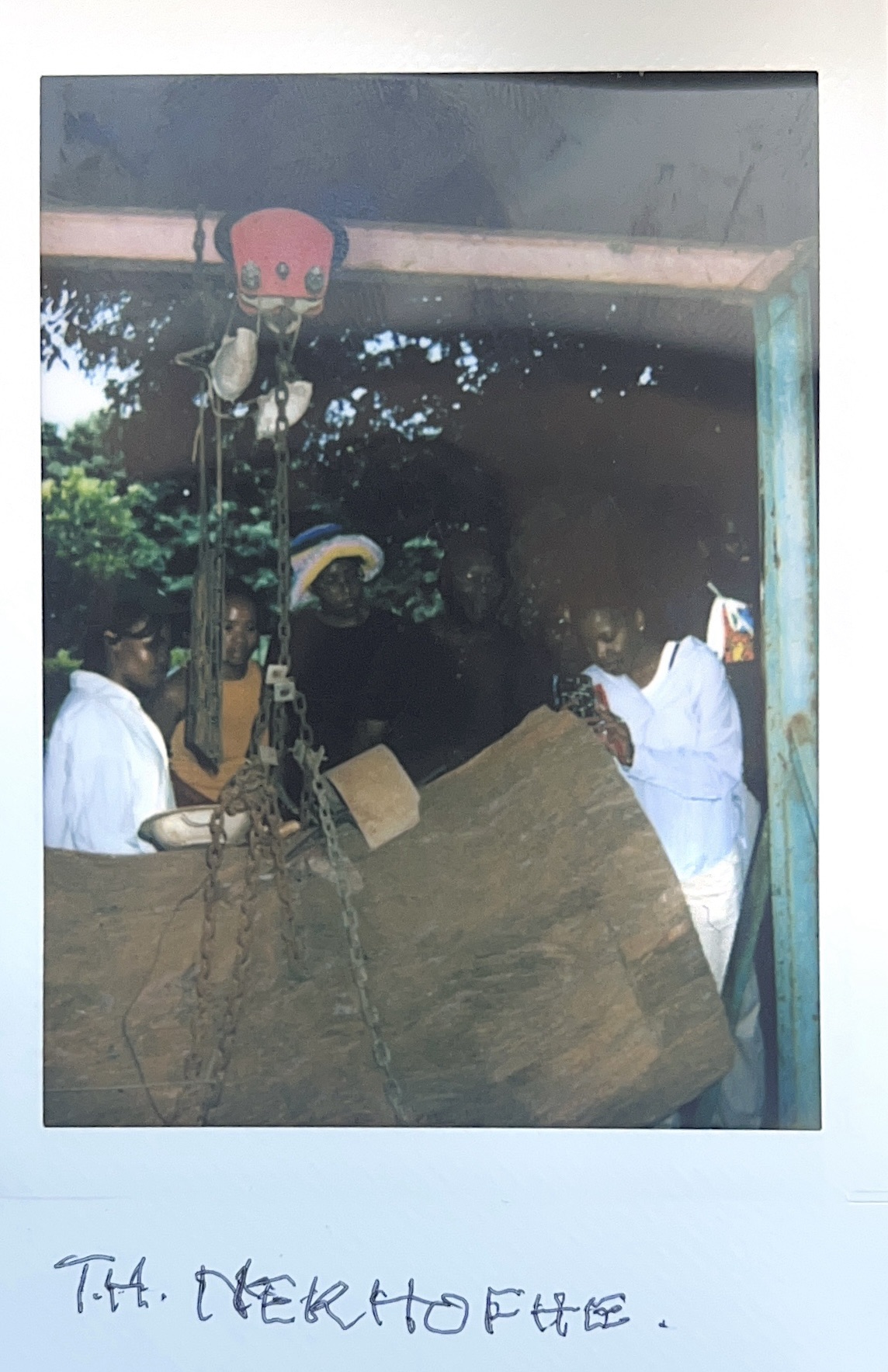

Later that same day, we visited the studio of renowned sculptor Hendrick Nekhofhe. His work is often rooted in scenes of everyday life, animals and cultural memory.

The visit felt less like a formal studio tour and more like sitting with a wise uncle. He affirmed each of us, insisting that we must never feel compelled to dilute or hold back our stories. That the world is big enough for our truths. That we are planted with gifts and that our task is simply to awaken them in order to give back to the world as it has given to us.

What became increasingly clear as we moved from studio to studio was that the artists’ homes announce them long before they do. Their practices spill into the yards, the gates and the landscape itself.

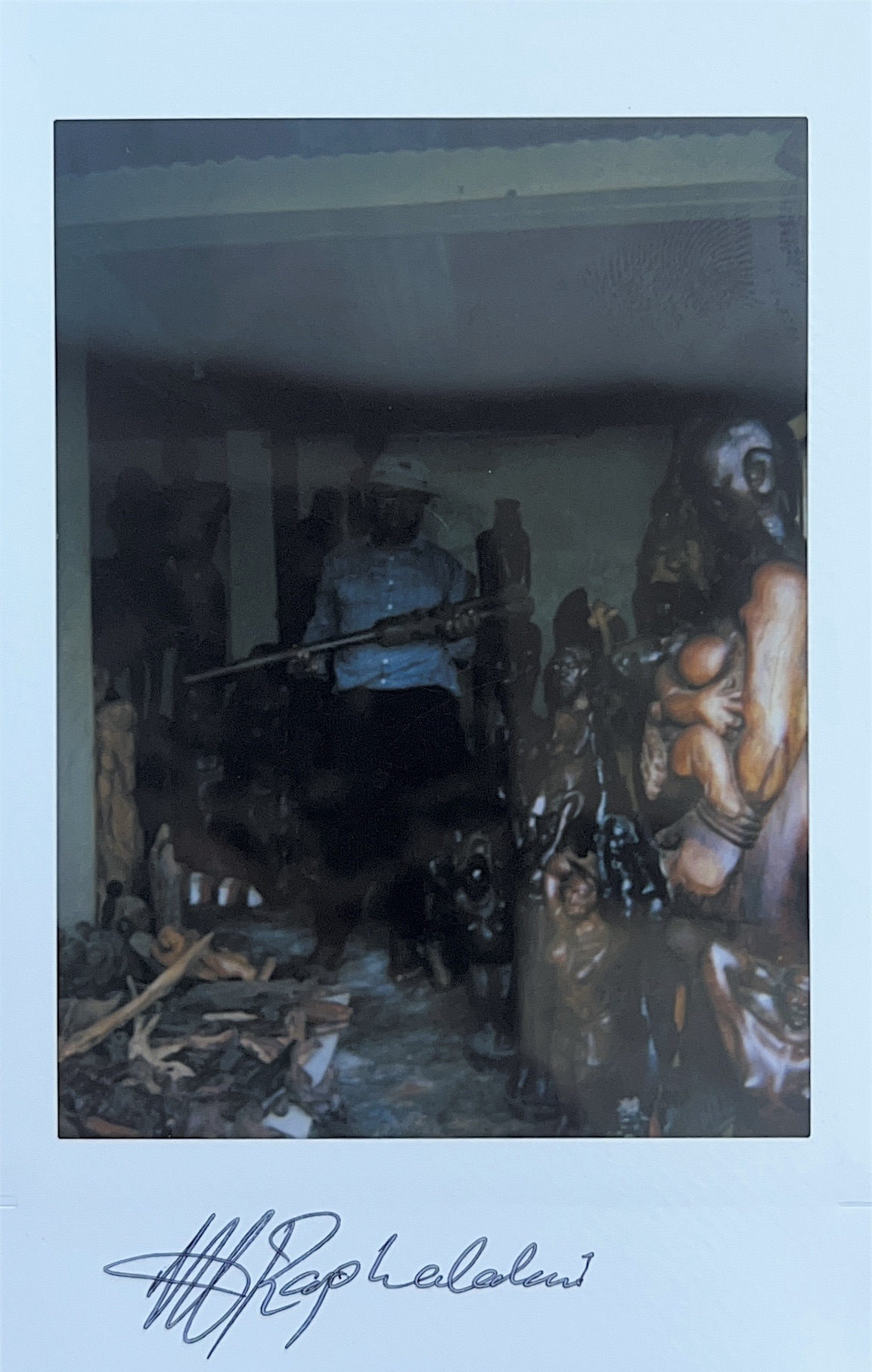

Arriving at Meshack Raphalalani’s home, we were met by wooden sculptures standing guard at the entrance. Before a word was exchanged or any introductions were made, we knew we had arrived.

But beyond the scale and presence of his sculptures lies a history of resistance.

During apartheid, Vho-Raphalalani used his work as a form of political commentary. His sculptures carried messages that could not be spoken freely in a time when speech was policed. Authorities would arrive to confiscate or destroy works deemed disruptive. The sculptures were not just artworks; they were evidence of thought, and thought under the apartheid regime was dangerous.

Standing in his yard surrounded by monumental works that now greet visitors openly, it felt impossible not to reflect on the resilience embedded in them.

Something was enchanting about the way the artists we visited throughout the week introduced their work, like children eager for a show and tell, unsure which piece to pick up first, which story to begin with. The excitement was unfiltered.

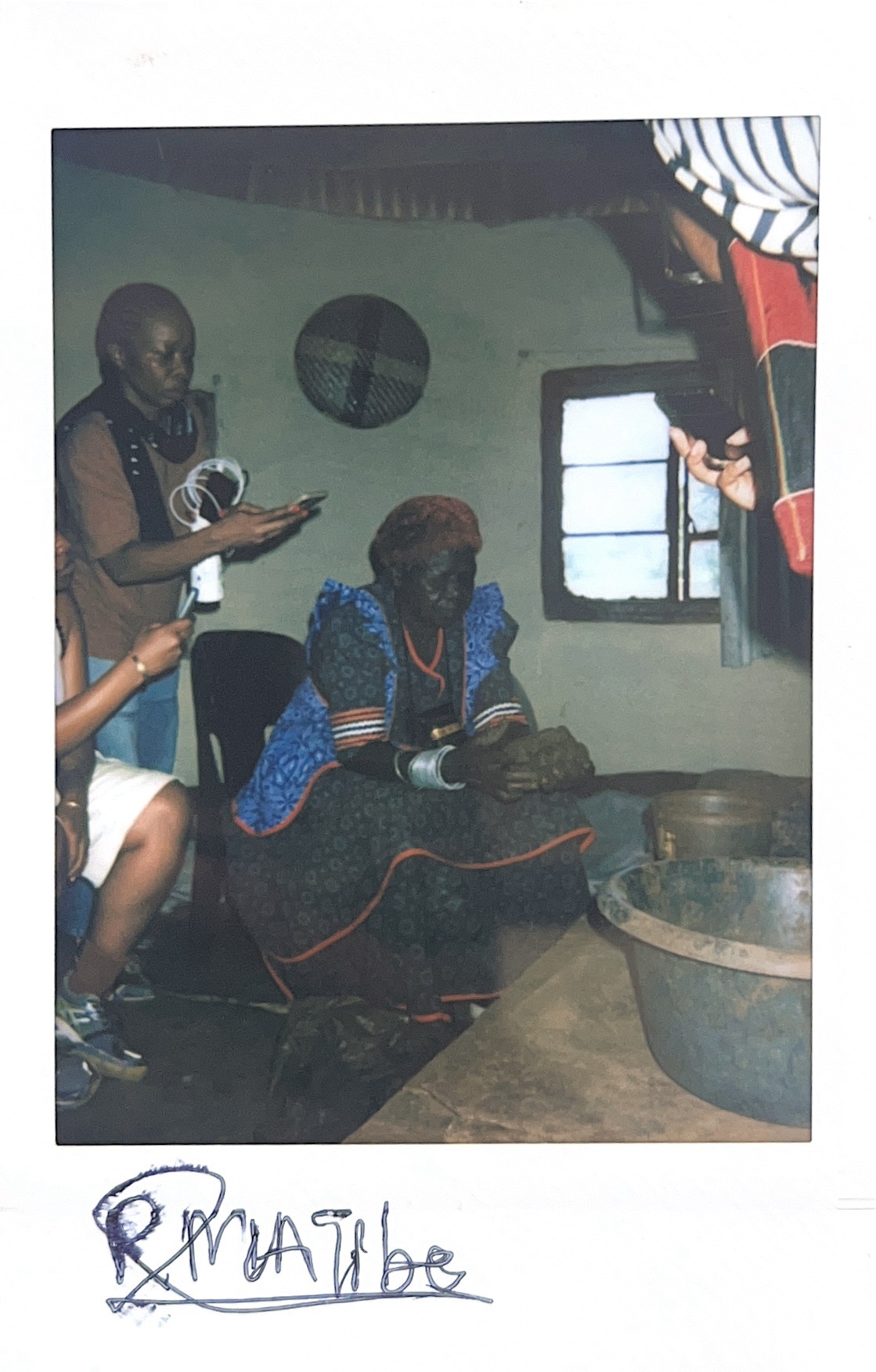

Despite the language barrier, Rebecca Matibe’s personality translated effortlessly. She was funny, assured diva, fully aware of the power of her hands.

She led us into her process without hesitation. From raw material to finished vessel, she demonstrated each step of her ceramic practice with a generosity that felt rare. Watching her shape clay from scratch was to witness muscle memory at work, knowledge carried not in textbooks, but in the body.

And yet, what stood out most was her curiosity. She was among the first to turn the attention back onto us, asking what each of the artists did, how they worked, and what stories they told. There was no hierarchy in her gaze only interest.

Her demonstration was long, though it felt brief. And at the end of it, she stood back, amused as we moved through her work in collective awe. We “fan-girled” openly, carefully selecting pieces to take home, carrying with us small fragments of her world.

Between studio visits and conversations with artists, we spent a day at Mapungubwe, widely recognised as the first indigenous kingdom of Southern Africa.

There is something surreal about standing where the earliest known society in the region once flourished. Mapungubwe was a thriving centre of trade, connected through networks that stretched far beyond its immediate geography. Standing at the summit of the mountain, gazing at the meeting point of Zimbabwe’s and Botswana’s borders, the idea of division felt almost artificial. The land does not recognise the borders we later imposed upon it. The river moves freely. In that space, the idea of “us” and “them” softened.

The last artist we visited was Noria Mabasa. An icon with a whole board directing us to her home, again, here the home announced her.

There is no easy word for someone like Vho-Mabasa. Visionary feels close, but not quite sufficient. She is often described as self-taught, but even that feels incomplete. According to her own telling, she began sculpting after receiving instruction through her dreams. There was no structured training, only a persistent spiritual prompting that guided her hands. What makes her extraordinary is not just that she dreamt the work, but that she trusted it.

To speak of her practice purely in technical terms would be to miss its essence. Vho-Mabasa’s work sits at the intersection of intuition, spirituality, and discipline. Even divine instruction requires labour.

Before departing Venda, we visited Mukondeni Pottery Village. A village is devoted to the practice and preservation of traditional pottery. Open to anyone willing to learn. For many of the women who work there, pottery is not simply a cultural expression; it is a livelihood. Their hands sustain households.

The week as a whole was deeply informative, but more than that, it was restorative. To be on the land, away from the hustle and bustle of the city, is to remember a different rhythm.

In returning to the land, to lineage, to material, we were reminded that culture is not something distant or abstract.

And perhaps what we carried back with us was not just documentation but responsibility.